Myrtles – the story of Robert and Clara

Clara Wieck grew up in a house filled with music and ambition. Her father Friedrich, a distinguished piano teacher and determined taskmaster, chose her name because it meant brilliant and bright, and from her earliest days set about ensuring it would come true.

And it did. Clara may not have spoken until she was four, but by the age of nine no-one was in doubt that she was a child prodigy pianist who could bear comparison with Mozart. By the age of 11, she was the talk of Leipzig after giving a sensational first public recital there in 1830. It was also the year in which the 20-year-old Robert Schumann – a brilliant-but-chaotic, not-quite-making-it musician – moved into the house to study with her father.

The two were instantly drawn to each other. Despite the age difference, they bonded over a shared love of music, literature, long country walks, spooky stories and a mutual need for closeness and companionship in the pressurised, high-achieving atmosphere of the Wieck household.

By 1835, when Clara was 16, we find Robert writing of ‘long hours spent in her arms’ and a deliriously happy Clara writing to her diary to record their first kiss. Friedrich Wieck’s priority, though, was Clara’s career, a fulfilment of all the brilliance he had planned for her. He wrote to Robert to sever all connections and whisked his daughter off on tour, extending her fame across Europe.

For almost two years, Robert and Clara did not see each other: he concentrated on trying to publish his latest piano compositions (daring and strange, still not quite ‘making it’), as well as sowing some wild oats; and she was busy being a star. Their feelings, though, were unchanged. Before long, secret letters were being exchanged through a mutual friend, and it was agreed that Clara’s 18th birthday was the moment when Robert would write to her father to ask for her hand in marriage.

Wieck reacted with rage, threatening to shoot Robert and banning all contact between him and his daughter. Music must come first! Schumann was a lazy drunkard, a mediocre composer, a treacherous pupil; he was owed a return on all he had invested in his brilliant daughter; and there was no way she would use her concert fees as a dowry.

After three years of secrecy and emotional turmoil, it all ended in court. In a case that dragged on for nearly a year, Robert and Clara behaved with dignity, diplomacy and steady determination. Wieck behaved like a lunatic. The final hearing went in favour of the star-crossed lovers and it was Robert’s turn to write to his diary: ‘From then on with her forever.’

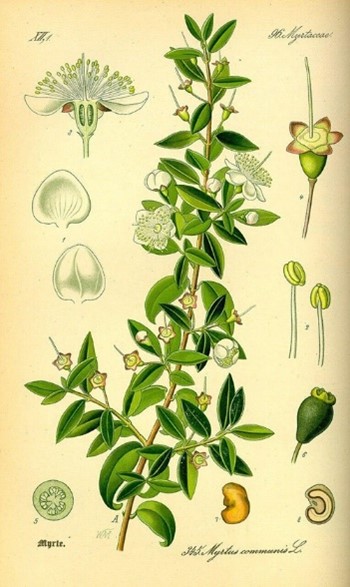

The marriage took place on 12th September 1840. The evening before, Robert presented Clara with a collection of songs he had been composing in secret for months, entitled Myrthen after the white myrtle sprigs that for centuries have symbolised love and hope in a bride’s wedding bouquet.

We can imagine Clara’s reaction as she opened the handsomely decorated volume (Robert had splashed out on a deluxe leather binding) and discovered 26 songs that added up to a kind of musical alphabet – an A-Z of their hopes, desires and experiences as a couple. Here were poems they had jointly treasured for years, with the great German writers of the day (Goethe, Rückert, Heine) nestled next to foreign poets like Lord Byron, Robert Burns and Thomas Moore. Here were riddles, humour, irony, nods to the Bible and the Qur’an, a mutual love of folksong. Here was a sense of their politics (liberal, progressive, internationalist) plus a magic-carpet ride to places that fascinated them – Persia, Scotland, Venice and Jerusalem. Myrthen was their story in song.

As well as celebrating a marriage, Myrthen also makes a series of symbolic marriages: between literature and music, Eastern and Western cultures, simplicity and sophistication, poetry and politics, the deeply personal and the proudly public. Because as anyone who ever made a mixtape for their partner in the 80s, or a Spotify playlist in more recent times, choosing songs for a lover is a way to express much more than purely musical enthusiasms. Feelings, desires, a sense of shared identity and much more can all be encoded through song curation, and the Schumanns were not the last couple who found this a way to communicate their deepest feelings.

Every song in this fabulously eccentric collection can just be enjoyed on its own terms. But they start to mean a lot more when you know the backstory. So for our performance of Schumann’s Myrtles next week, Harriet Burns and Nick Pritchard will be singing a new English translation by Jeremy Sams, while the context is explored in a series of newly commissioned poems written and read by Kate Wakeling.

Robert recalled ‘laughing and weeping for joy’ as he assembled this ‘imperfect garland’ for his new wife. Clara was no less thrilled and amazed by his new songs.

We hope you can come and enjoy them too.

Christopher Glynn